Signers of the Constitution

This information is scanned from Souvenir and Official Programme of the Centennial Celebration of George Washington’s Inauguration as First President of the United States, compiled and edited by John Alden; Published by Garnett & Gow, New York, copyrighted, 1889.

As has been conclusively shown in a preceding chapter, [not included in this electronic version] no body of statesmen ever assembled tinder conditions making more serious demands upon their patriotism, temperateness and unselfishness than those which confronted the members of the Constitutional Convention, which was called to order in the state-house at Philadelphia on Sept. 17, 1787. Other centuries must come and go before even the most diligent and the most philosophical of historians can gain a comprehensive view of the results which have sprung from the labors of that convention. Those results, even at present writing, have extended far beyond the limits of our own continent. They are by no means confined in their beneficence to the English-speaking nations of the earth. India’s countless millions join with the natives of the Emerald Isle in demanding “those powers of local self-government which every State in the American Union possesses, and which Ireland does not possess. France is just beginning to see in a constitution analogous to ours a remedy for those evils which have been baffling her most disinterested statesmen ever since the First Directory. Every one of the South American republics has made our constitution its model rather than that great unwritten fundamental law of England, in spite of the fact that in reciprocal trade relations every one of those countries is closer to Great Britain than to the United States. Australia has united with the Dominion of Canada in requiring from the mother country almost absolute autonomy in local affairs. From Alaska to the Argentine Republic, and from Cape Colony to the Shetland Isles, is accepted our demonstration of the proposition that e pluribus unum means nothing but the only perpetuity practicable for the rightful powers of the many. This leaven is still working. What has been done we can imperfectly analyze. What is to be, is beyond our ken.

The men who forged this hammer which was to deliver mankind from oppression by breaking down forever the labyrinthine walls of that ancient superstition that law and order are incompatible with liberty, were excellent types of the American civilization of a hundred years ago. Of the lives of many of them, we have but little record. In some cases, dates of births are uncertain. In some, even the year of death is unknown. Often, the historian finds no trace of any public service performed outside of the convention. Some giants are noted, of course. Europe vies with America in honoring Franklin’s memory. Washington’s name adds lustre even to the work done at Philadelphia in 1787. No student of governmental development in general can ignore Alexander Hamilton; and Patrick Henry, though not a signer of the Constitution, divides with James Madison, its great exponent, the honor of having contributed most valuable suggestions while the convention was in session. Jay, too, though not a delegate, has a name inseparably associated with that momentous document. But the majority of the delegates are hardly should be. The following sketches are as full as the information that was at hand would warrant. They contain all know facts about the lives of the signers of the Constitution. Neither Washington nor Madison is included here, because biographical sketches of both will be found with those of other Presidents of the United States in another chapter.

It would be unfair not to mention here some of the most prominent members of the convention, who, for various reasons did not affix their names to the Constitution after it had been drawn up. The document was, of course, a compromise. Ideas of those who finally opposed it were conditions which is framers could not afford to overlook, and did not overlook. Divisions in the convention were on several different lines. Small States were jealous of large ones. Georgia and South Carolina were distrustful of New England Puritanism. New York had established a custom-house of her own, and had a direct selfish interest in keeping from the general government that power to regulate commerce, which was regarded as essential to it, by all the other States. Within each one of the commonwealths there was an issue between those who believed in absolute localization of power, and those who held to the theory of centralization. The latter difference was the one on which the division between Federalists and Republicans was based, and which may fairly be held to have been maintained as the real issue between great parties under various party names up to the present time. It is not just, therefore, to condemn the men who failed to sign the Constitution, and those who opposed it in the various State conventions. Patrick Henry was one of the foremost of its opponents in Virginia. A purer patriot never lived. Edmund Randolph, one of the most valuable members of the convention, refused to sign. Elbridge Gerry, of Massachusetts, did the same. He honestly believed that the rights of the people were inadequately guaranteed. George Mason, of Virginia, the intimate friend and neighbor of Washington, agreed with Gerry. Caleb Strong of Massachusetts, Oliver Ellsworth, of Connecticut, William Churchill Houston, of New Jersey, George Wythe and James McClurg of Virginia, John Francis Mercer, of Maryland, Luther Martin of New Jersey, Alexander Martin, of North Carolina, and William Richardson Davies, of South Carolina, and William Pierce William Houston, of Georgia, did not sign because they were not present on the last day of the convention.

The action of Yates and Lansing, of New York, in withdrawing from the convention, met with a large amount of contemporaneous criticism. It left Hamilton alone, without a vote, and disfranchised New York absolutely. But the characters of the delegates who went out do nor warrant the theory that their motive was to flourish as demagogues on the sentiment in favor of keeping up New York’s custom-house at the expense of the permanent interests of the whole American people. It is more charitable to believe that, like Randolph and Mason and Gerry, they were sincere, though mistaken patriots. This course, however, led to the new combinations in the convention. On the question of delaying the abolition of the slave-trade, and of slave representation, Maryland, Delaware, South Carolina, and Georgia were on one side; Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, New Jersey and Pennsylvania were on the other. Virginia and North Carolina held the balance of power after New York was left without a vote. The former was controlled by men who were opposed to slavery on principle. The latter was divided. With New York’s vote in the affirmative, there is little doubt that the slave-trade would have been immediately abolished, and that each State would have had a representation based on its voting population. South Carolina and Georgia wanted a full representation of the slave population, and preferred no restriction of the trade. Virginia stood in the breach when New York had withdrawn. Her delegation, made up of men more devoted to the general interest than to the specific interest of Virginia, or of their own estates, men who commanded universal respect because of their talents as well as their unselfishness, were inclined to consent to nothing which could be expected to endanger the future of the republic, or to throw doubt upon the consistency of those who were advocating liberty for all men. So the compromise was secured, which gave Congress power to stop the slave-trade 1808, though it left to the States all action with reference to the institution of slavery within their borders.

It was decided, after much debate, not to leave the ratification of the Constitution to State Legislatures, because what one Legislature had accepted, another might, with equal propriety, reject. State conventions were to be called for the purpose of making such ratifications. Thus the people of each State, and not the State as a government entity, were to accept the Constitution.

Debates in the Convention covered a great range of topics, and involved dissension on small as well as great matters. But as a rule they were thoroughly dignified in their tone. Mason, the Virginian opponent of slavery, was one of the most earnest debaters on the issue of slave representation. He was opposed from the bottom of the Nation’s fundamental law. It is rather a curious fact that on this point he was met with the ironical opposition of Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut, who thought any possible solution of this question better than anarchy.

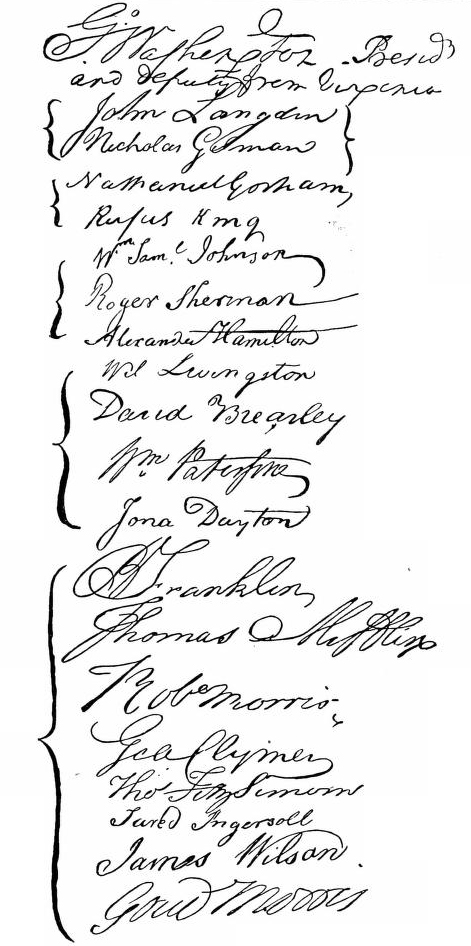

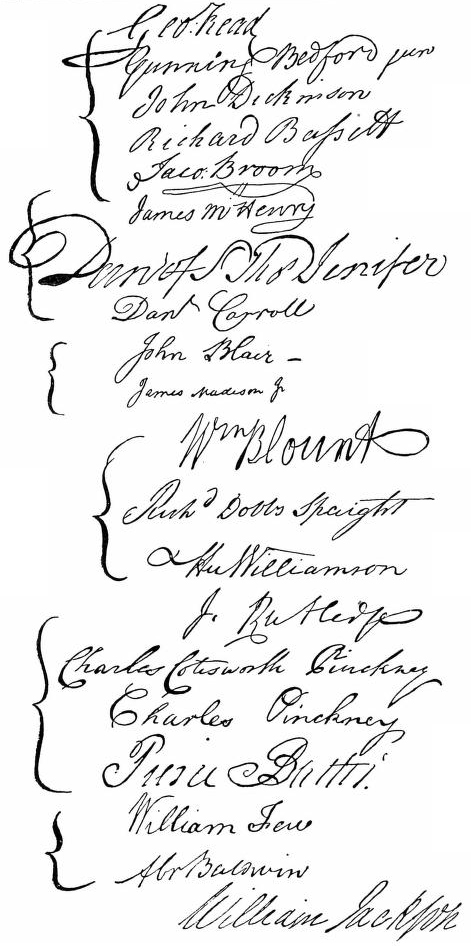

Here are the signatures of members of the convention exactly as affixed to the Constitution:

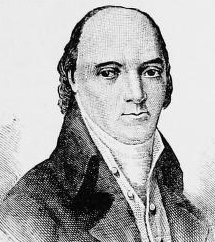

RICHARD DOBBS SPAIGHT – NORTH CAROLINA

RICHARD DOBBS SPAIGHT was born at Newbern, North Carolina, in 1758. He was a son of wealthy parents and was sent abroad at the age of nine years to be educated. He did not return to his country until 1778 -two years after the Declaration of Independence had been signed and the Revolutionary war begun. He was then only twenty years of age, but his sympathies were strongly aroused on behalf of the colonies, and he at once repaired to the camp of Gov. Caswell and joined the army. He was made one of the Governor’s Aids and participated with distinction in the battle of Camden. From 1781 to 1783 he was a member of the State Legislature, and the latter year was elected a delegate to Congress. He served in Congress until 1786, and was then chosen as one of the delegates from North Carolina to the Constitutional Convention. Spaight was the youngest of all the delegates who took an active part in the deliberations of that body. He was in favor of a presidential term of seven years instead of four, and proposed the election of United States Senators by the Legislatures of the several States. Though not altogether suited by the form of Government at last determined upon, he supported it warmly both in and out of the convention. He failed, however, in his own State. After living for several years in the West Indies, in order to regain his health, he was Governor of his State for three years 1792 to 1795– and a member of Congress from 1798 to 1801. Beaten for reelection he was challenged by John Stanley, his successful competitor, and was mortally wounded in a duel on September 5th, 1802. He died before the day was over.

RICHARD DOBBS SPAIGHT was born at Newbern, North Carolina, in 1758. He was a son of wealthy parents and was sent abroad at the age of nine years to be educated. He did not return to his country until 1778 -two years after the Declaration of Independence had been signed and the Revolutionary war begun. He was then only twenty years of age, but his sympathies were strongly aroused on behalf of the colonies, and he at once repaired to the camp of Gov. Caswell and joined the army. He was made one of the Governor’s Aids and participated with distinction in the battle of Camden. From 1781 to 1783 he was a member of the State Legislature, and the latter year was elected a delegate to Congress. He served in Congress until 1786, and was then chosen as one of the delegates from North Carolina to the Constitutional Convention. Spaight was the youngest of all the delegates who took an active part in the deliberations of that body. He was in favor of a presidential term of seven years instead of four, and proposed the election of United States Senators by the Legislatures of the several States. Though not altogether suited by the form of Government at last determined upon, he supported it warmly both in and out of the convention. He failed, however, in his own State. After living for several years in the West Indies, in order to regain his health, he was Governor of his State for three years 1792 to 1795– and a member of Congress from 1798 to 1801. Beaten for reelection he was challenged by John Stanley, his successful competitor, and was mortally wounded in a duel on September 5th, 1802. He died before the day was over.

DANIEL OF ST. THOMAS JENIFER – MARYLAND

DANIEL OF ST. THOMAS JENIFER was born in 1733. He was a native of Maryland, a colony which had been the first to accept those principles of religious equality upon which the new Constitution came to be so largely founded. Made up in large measure of English Catholics, upon whom the ban of proscription had been laid by a State Church, the colonists of Maryland had no desire to similarly persecute any other sect. Unlike the Puritans of Massachusetts, it cannot truly be said of them that they came to America in order to gain an opportunity of worshiping God in accordance with the dictates of their own consciences and of preventing other people from doing the same. Their logical liberality found a parallel only in that of Roger Williams, who had founded the Providence Plantations on exactly the same principles. In such a state of society, no secion of the people being barred out from participation in the front, and it is not remarkable that such men as Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer made themselves felt. In brilliant statesmen Maryland was not so rich as Virginia. But the men prominent in the politics of the former colony were remarkable for their God-fearing integrity. Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer was a man of liberal education, and had, even before the Revolution, been prominent in the politics of the colony. He served in Congress from 1778 to 1782, and was one of the most valuable members of that body. He was a regular attendant on the sessions of the Constitutional Convention. He died in 1790.

DANIEL OF ST. THOMAS JENIFER was born in 1733. He was a native of Maryland, a colony which had been the first to accept those principles of religious equality upon which the new Constitution came to be so largely founded. Made up in large measure of English Catholics, upon whom the ban of proscription had been laid by a State Church, the colonists of Maryland had no desire to similarly persecute any other sect. Unlike the Puritans of Massachusetts, it cannot truly be said of them that they came to America in order to gain an opportunity of worshiping God in accordance with the dictates of their own consciences and of preventing other people from doing the same. Their logical liberality found a parallel only in that of Roger Williams, who had founded the Providence Plantations on exactly the same principles. In such a state of society, no secion of the people being barred out from participation in the front, and it is not remarkable that such men as Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer made themselves felt. In brilliant statesmen Maryland was not so rich as Virginia. But the men prominent in the politics of the former colony were remarkable for their God-fearing integrity. Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer was a man of liberal education, and had, even before the Revolution, been prominent in the politics of the colony. He served in Congress from 1778 to 1782, and was one of the most valuable members of that body. He was a regular attendant on the sessions of the Constitutional Convention. He died in 1790.

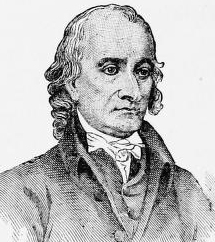

HUGH WILLIAMSON – NORTH CAROLINA

HUGH WILLIAMSON, of North Carolina, was born of Irish parents in Chester Co., Penn., in 1735. His early education was a thoroughly one, and after careful preparatory training he entered the College of Philadelphia, from which institution he graduated in 1757. He began at once the study Divinity, and secured a license to preach, but as near as can he learned from the fragments of his biography handed down to posterity, his work in the pulpit and in the parish was satisfactory neither to himself nor his friends. After much prayerful consideration of the subject he decided to study medicine, and carried out that resolve. In the work and the science of a physician he was more than ordinarily successful. Appointed Professor of Medicine in his own Alma Mater in 1760, he spent four years there and then went to Europe with the purpose of studying at Edinburgh, London and Utrecht. From the University in the latter city he obtained the degree of M. D. On his return to Philadelphia he soon secured an excellent practice, was chosen a member of the American Philosophical Society, and was one of the commissioners of that society to observe the transit of Venus in 1767. He visited the West Indies in 1772, and then went to London with the idea of procuring assistance for an Academy at Newark, N. J. While there in 1774 he was examined before the Privy Council on the subject of that famous “tea-party in Boston Harbor.” He settled at Edenton, North Carolina, in 1777, having gone there with a younger brother who was engaged in business. He was made Medical Director of the North Carolina forces in 1779, and was elected in 1782 to the House of Commons and afterwards to Congress, in which he served one term under the Constitution. He died in New York in 1819.

HUGH WILLIAMSON, of North Carolina, was born of Irish parents in Chester Co., Penn., in 1735. His early education was a thoroughly one, and after careful preparatory training he entered the College of Philadelphia, from which institution he graduated in 1757. He began at once the study Divinity, and secured a license to preach, but as near as can he learned from the fragments of his biography handed down to posterity, his work in the pulpit and in the parish was satisfactory neither to himself nor his friends. After much prayerful consideration of the subject he decided to study medicine, and carried out that resolve. In the work and the science of a physician he was more than ordinarily successful. Appointed Professor of Medicine in his own Alma Mater in 1760, he spent four years there and then went to Europe with the purpose of studying at Edinburgh, London and Utrecht. From the University in the latter city he obtained the degree of M. D. On his return to Philadelphia he soon secured an excellent practice, was chosen a member of the American Philosophical Society, and was one of the commissioners of that society to observe the transit of Venus in 1767. He visited the West Indies in 1772, and then went to London with the idea of procuring assistance for an Academy at Newark, N. J. While there in 1774 he was examined before the Privy Council on the subject of that famous “tea-party in Boston Harbor.” He settled at Edenton, North Carolina, in 1777, having gone there with a younger brother who was engaged in business. He was made Medical Director of the North Carolina forces in 1779, and was elected in 1782 to the House of Commons and afterwards to Congress, in which he served one term under the Constitution. He died in New York in 1819.

ROBERT MORRIS – PENNSYLVANIA

ROBERT MORRIS, of Pennsylvania, born in England, in 1734 and was brought to this country by his father when a child. They settled first in Maryland, but afterwards came to Philadelphia, when the boy entered the establishment of Charles Willing, a well known merchant, and was admitted to a partnership in 1754. The firm became the most prosperous importing house in the colonies and was not dissolved until 1793. No man made greater personal sacrifices than Robert Morris in helping to secure liberty for America. The largest of importers he opposed the Stamp Act and signed the non-importation agreement. He was vice-president of the Committee of Safety, until the dissolution of that body in 1776. Morris appears to have had some doubt as to the advisability of the Declaration of Independence. He voted against it first, and remained away from the session on July 4th, 1776. But on August 2, when the engrossed copy of the Declaration had been received, he affixed his signature, in order to show that he had not been actuated, in his reluctance by any motives of personal expediency. During the Revolution, an Italian historian has said, that the Americans owed as much to the financial operations of Morris as to the diplomatism of Franklin, or the arms of George Washington. He was made Superintendent of Finance in 1781, and in accepting the position, said, “The United States may command everything I have except my integrity.” He used his own funds freely for the public service. The Bank of North America was established by him. He was chosen United States Senator in 1788, having declined the Secretaryship of the Treasury. Speculation made him poor, and he spent three years in a debtors’ prison. He died in 1806.

ROBERT MORRIS, of Pennsylvania, born in England, in 1734 and was brought to this country by his father when a child. They settled first in Maryland, but afterwards came to Philadelphia, when the boy entered the establishment of Charles Willing, a well known merchant, and was admitted to a partnership in 1754. The firm became the most prosperous importing house in the colonies and was not dissolved until 1793. No man made greater personal sacrifices than Robert Morris in helping to secure liberty for America. The largest of importers he opposed the Stamp Act and signed the non-importation agreement. He was vice-president of the Committee of Safety, until the dissolution of that body in 1776. Morris appears to have had some doubt as to the advisability of the Declaration of Independence. He voted against it first, and remained away from the session on July 4th, 1776. But on August 2, when the engrossed copy of the Declaration had been received, he affixed his signature, in order to show that he had not been actuated, in his reluctance by any motives of personal expediency. During the Revolution, an Italian historian has said, that the Americans owed as much to the financial operations of Morris as to the diplomatism of Franklin, or the arms of George Washington. He was made Superintendent of Finance in 1781, and in accepting the position, said, “The United States may command everything I have except my integrity.” He used his own funds freely for the public service. The Bank of North America was established by him. He was chosen United States Senator in 1788, having declined the Secretaryship of the Treasury. Speculation made him poor, and he spent three years in a debtors’ prison. He died in 1806.

WILLIAM SAMUEL JOHNSON – CONNECTICUT

ONE of the most scholarly members of the convention was WILLIAM SAMUEL JOHNSON, of Connecticut. Born at Stratford, in 1727, he was the son of a college President, who had resigned the management of King’s College, N. Y., and graduated himself Yale College, his father’s Alma Mater, in 1744. Johnson studied law, after his admission to bar distinguished himself by eloquence as a pleader, and effectiveness as a cross-examiner. His first official position was that of delegate in the Provincial Congress, to which he was elected in 1765. He lived in England as the agent of his colony from 1766 to 1771, was a judge of Connecticut’s Supreme Court from 1772 to 1774, and after the Revolution served in the Continental Congress from 1784 to 1787. In the Constitutional Convention, Mr. Johnson was the first to suggest the Senate, an independent legislative body, as a feature of the form of government to be adopted. He was a firm believer in the English theory, of a double-house Legislature, and his ideas were accepted. After the Constitution went into effect Mr. Johnson was made United States Senator from his State, and was one of the hardest workers in developing the bill upon which the whole of the judiciary system of the United States is founded. He was President of Columbia College for eleven years, from 1789 to 1800. He died at a ripe old age, on on Nov. 14, 1819.

ONE of the most scholarly members of the convention was WILLIAM SAMUEL JOHNSON, of Connecticut. Born at Stratford, in 1727, he was the son of a college President, who had resigned the management of King’s College, N. Y., and graduated himself Yale College, his father’s Alma Mater, in 1744. Johnson studied law, after his admission to bar distinguished himself by eloquence as a pleader, and effectiveness as a cross-examiner. His first official position was that of delegate in the Provincial Congress, to which he was elected in 1765. He lived in England as the agent of his colony from 1766 to 1771, was a judge of Connecticut’s Supreme Court from 1772 to 1774, and after the Revolution served in the Continental Congress from 1784 to 1787. In the Constitutional Convention, Mr. Johnson was the first to suggest the Senate, an independent legislative body, as a feature of the form of government to be adopted. He was a firm believer in the English theory, of a double-house Legislature, and his ideas were accepted. After the Constitution went into effect Mr. Johnson was made United States Senator from his State, and was one of the hardest workers in developing the bill upon which the whole of the judiciary system of the United States is founded. He was President of Columbia College for eleven years, from 1789 to 1800. He died at a ripe old age, on on Nov. 14, 1819.

JOHN LANGDON – NEW HAMPSHIRE

JOHN LANGDON, of New Hampshire, was 48 years of age when the Constitutional Convention met. A native of Portsmouth, he had only the advantage of a common-school education supplemented by a mercantile training that early made him one of the foremost men in the commercial circles of his own colony. He was also one of the first to espouse the Revolutionary cause. With John Sullivan he assisted in carrying off the military stores from Fort William and Mary in 1774. He was chosen a member of the Continental Congress one year later, but soon resigned to become a Navy Agent. Then he became speaker of the Colonial Legislature, and afterwards a Judge of the Court of Common Pleas. Mr. Langdon was a close personal friend of Gen. Stark, and pledged his own property to raise money for the expedition which resulted in the victory at Bennington. He served himself in the army afterwards. In 1779 he was President of the State Constitutional Convention. He went back to Congress in 1783, and in 1785 was elected “President” of New Hampshire. After the document which made the United States a Nation had gone into effect, Mr. Langdon was made Temporary President of the first Federal Congress, and in that capacity notified Gen. Washington of his election to the Presidency. As Governor of New Hampshire, and then as United States Senator, he maintained his claim to the respect of his fellow citizens. He declined the Secretaryship of the Navy in 181, and the Vice-Presidency of the United States in 1812. He died on Sept. 18, 1819.

JOHN LANGDON, of New Hampshire, was 48 years of age when the Constitutional Convention met. A native of Portsmouth, he had only the advantage of a common-school education supplemented by a mercantile training that early made him one of the foremost men in the commercial circles of his own colony. He was also one of the first to espouse the Revolutionary cause. With John Sullivan he assisted in carrying off the military stores from Fort William and Mary in 1774. He was chosen a member of the Continental Congress one year later, but soon resigned to become a Navy Agent. Then he became speaker of the Colonial Legislature, and afterwards a Judge of the Court of Common Pleas. Mr. Langdon was a close personal friend of Gen. Stark, and pledged his own property to raise money for the expedition which resulted in the victory at Bennington. He served himself in the army afterwards. In 1779 he was President of the State Constitutional Convention. He went back to Congress in 1783, and in 1785 was elected “President” of New Hampshire. After the document which made the United States a Nation had gone into effect, Mr. Langdon was made Temporary President of the first Federal Congress, and in that capacity notified Gen. Washington of his election to the Presidency. As Governor of New Hampshire, and then as United States Senator, he maintained his claim to the respect of his fellow citizens. He declined the Secretaryship of the Navy in 181, and the Vice-Presidency of the United States in 1812. He died on Sept. 18, 1819.

ROGER SHERMAN – CONNECTICUT

ROGER SHERMAN, of Connecticut, was a native of Newton, Massachusetts, and was born in 1721. He represented the wisdom of the common people rather than the knowledge of the upper classes in the Convention. Mr. Sherman was a shoemaker by trade and, because of the death of his father, had bee compelled, at an early age to assume the support his mother and of several younger children. The spirit of study and of self improvement led him to fit himself for the position of County Surveyor, which he he held for several years. He studied law long after he had reached middle life, and so great was his power of application, together with his natural capacity, that he rose to be a Judge of the Supreme Court. He was terse, not ornate, in speech; and a cogent thinker. Mr. Sherman was one of the signers of the- Declaration of Independence, a member of the Continental Congress during the war. His work in codifying the laws of Connecticut in 1783 was of lasting service to the State. He signed the Articles of Association of Congress and the Articles of Confederation, as well as the Declaration and the Constitution; and is said to be the only man whose name appears on all four of those documents. Jefferson used to say of Roger Sherman, that he never said a foolish thing in his life. Mr. Sherman died on July 23, 1793 at New Haven, Connecticut.

ROGER SHERMAN, of Connecticut, was a native of Newton, Massachusetts, and was born in 1721. He represented the wisdom of the common people rather than the knowledge of the upper classes in the Convention. Mr. Sherman was a shoemaker by trade and, because of the death of his father, had bee compelled, at an early age to assume the support his mother and of several younger children. The spirit of study and of self improvement led him to fit himself for the position of County Surveyor, which he he held for several years. He studied law long after he had reached middle life, and so great was his power of application, together with his natural capacity, that he rose to be a Judge of the Supreme Court. He was terse, not ornate, in speech; and a cogent thinker. Mr. Sherman was one of the signers of the- Declaration of Independence, a member of the Continental Congress during the war. His work in codifying the laws of Connecticut in 1783 was of lasting service to the State. He signed the Articles of Association of Congress and the Articles of Confederation, as well as the Declaration and the Constitution; and is said to be the only man whose name appears on all four of those documents. Jefferson used to say of Roger Sherman, that he never said a foolish thing in his life. Mr. Sherman died on July 23, 1793 at New Haven, Connecticut.

JAMES WILSON – PENNSYLVANIA

JAMES WILSON, of Pennsylvania, was born in 1740, and was a native of Scotland. He had had a thorough education in the greatest universities of his native country before he emigrated to America in 1761, at the age of twenty-one years. He went first to New York, but finding that his classical acquirements were not fully appreciated there he removed, after about five years, to Philadelphia, where, for a time, he served as tutor in the City College. He then studied law in the office of John Dickinson, and tried the practice of his profession in several smaller towns– Reading, Carlisle and Annapolis, without much success. He returned to Philadelphia and was admitted to the bar there in 1778. During and after the Revolution he was for six years a member of Congress. He was a brilliant orator. as well as a learned man, and in the Constitutional Convention made himself felt as one of the strongest men on the Pennsylvania delegation. In the State Convention called to ratify the Constitution Wilson was a most prominent figure. His influence is sometimes credited with having prevented the rejection of the document by that body. Appointed as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court by President Washington, in 1789, he resigned in 1790 to take charge of the Law Department in the University of Pennsylvania. He felt that no man’s energies could be better spent than in the instruction of youth. Like Robert Morris, James Wilson was reduced to financial ruin by land speculation. He was thrown into a debtor’s prison on the snit of Pierce Butler, who had served with him in the Constitutional Convention. For months he lay there, broken in body and in mind, and when Mr. Butler finally ordered his release he died before it could be accomplished. His death occurred in 1798.

JAMES WILSON, of Pennsylvania, was born in 1740, and was a native of Scotland. He had had a thorough education in the greatest universities of his native country before he emigrated to America in 1761, at the age of twenty-one years. He went first to New York, but finding that his classical acquirements were not fully appreciated there he removed, after about five years, to Philadelphia, where, for a time, he served as tutor in the City College. He then studied law in the office of John Dickinson, and tried the practice of his profession in several smaller towns– Reading, Carlisle and Annapolis, without much success. He returned to Philadelphia and was admitted to the bar there in 1778. During and after the Revolution he was for six years a member of Congress. He was a brilliant orator. as well as a learned man, and in the Constitutional Convention made himself felt as one of the strongest men on the Pennsylvania delegation. In the State Convention called to ratify the Constitution Wilson was a most prominent figure. His influence is sometimes credited with having prevented the rejection of the document by that body. Appointed as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court by President Washington, in 1789, he resigned in 1790 to take charge of the Law Department in the University of Pennsylvania. He felt that no man’s energies could be better spent than in the instruction of youth. Like Robert Morris, James Wilson was reduced to financial ruin by land speculation. He was thrown into a debtor’s prison on the snit of Pierce Butler, who had served with him in the Constitutional Convention. For months he lay there, broken in body and in mind, and when Mr. Butler finally ordered his release he died before it could be accomplished. His death occurred in 1798.

JOHN DICKINSON – DELAWARE

JOHN DICKINSON, of Delaware, was born in Maryland in 1732. His father was a man of wealth who had sent two older sons to be educated in England. Both had died there, and the father decided, for his youngest Son, to be satisfied with the educational institutions of the colonies. Soon after the birth of the latter. the family removed to Dover, Delaware. The son, after completing his scholastic training, studied law in the office of John Moland, at Philadelphia, and then went to England, where he spent three years at the Temple, in London to give himself greater familiarity with the common law. He returned to this country and began the practice of law in the city were he had first studied. He was sent to the Assembly of Pennsylvania in 1764 and in 1765 was a member of the general Congress which met in New York to protest against English tyranny. Two years later Dickinson published his “Farmer’s Letters ” on the illegality of British taxation, which were so widely read and produced so profound an impression that their author soon took rank among the most effective of American writers. They were translated into French, and were also published in England with a preface by Benjamin Franklin. In 1774 Dickinson became a member of Congress. He refused to sign the Declaration of Independence in 1776, but took up arms in behalf of liberty in 1777, and was made a brigadier-general in the service of Pennsylvania by Gov. McKean. He went back to Congress in 1779, in 1780 was elected President of Delaware, and in 1782 was made President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. In 1785 he permanently removed to Delaware. His nine ” Fabius” letters in favor of the Constitution were very effective. He died in 1808.

JOHN DICKINSON, of Delaware, was born in Maryland in 1732. His father was a man of wealth who had sent two older sons to be educated in England. Both had died there, and the father decided, for his youngest Son, to be satisfied with the educational institutions of the colonies. Soon after the birth of the latter. the family removed to Dover, Delaware. The son, after completing his scholastic training, studied law in the office of John Moland, at Philadelphia, and then went to England, where he spent three years at the Temple, in London to give himself greater familiarity with the common law. He returned to this country and began the practice of law in the city were he had first studied. He was sent to the Assembly of Pennsylvania in 1764 and in 1765 was a member of the general Congress which met in New York to protest against English tyranny. Two years later Dickinson published his “Farmer’s Letters ” on the illegality of British taxation, which were so widely read and produced so profound an impression that their author soon took rank among the most effective of American writers. They were translated into French, and were also published in England with a preface by Benjamin Franklin. In 1774 Dickinson became a member of Congress. He refused to sign the Declaration of Independence in 1776, but took up arms in behalf of liberty in 1777, and was made a brigadier-general in the service of Pennsylvania by Gov. McKean. He went back to Congress in 1779, in 1780 was elected President of Delaware, and in 1782 was made President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. In 1785 he permanently removed to Delaware. His nine ” Fabius” letters in favor of the Constitution were very effective. He died in 1808.

GOUVERNEUR MORRIS – PENNSYLVANIA

GOUVERNEUR MORRIS, of Pennsylvania, was born in Morrisania. N.Y., in 1752. He enjoyed the best education that the colonies afforded, and graduated with high honors from Columbia College at the age of sixteen years. Then he studied law in the office of Wm. Smith, a well-known barrister, who afterwards became Chief Justice of the Province of New York. At the age of nineteen years, in 1771, he was admitted to the Provincial bar. In 1775, after devoting a great deal of attention to public affairs, Mr. Morris was elected a member of the Provincial Congress, and three years later was sent to the Continental Congress. The delegates of New York were not empowered to sign the Declaration of Independence until after the meeting of the State Convention on July 9, 1776. On that day the convention having received a copy of the Declaration passed a resolution of approval, and directed Governeur Morris to write an answer notifying the delegates of this action. Mr. Morris was known as one of the earliest opponents of domestic slavery in New York State, and look a large part in drafting the Constitution of that State. In 1778, as a member of Congress, he was made a mem her of several committees on military supplies, and became a C1ose personal friend of General Washington. Deserted by his own family because of his zeal in behalf of the patriot cause, he made up his mind to take up a permanent residence in Philadelphia. He lost a leg because of an accident in 1780. He was Assistant Superintendent of Finance under Robert Morris for three and a half years. In 1788, he went to France, and was the only member of the diplomatic corps who remained in Paris. On his return to America he was elected a member of the United States Senate from New York, after again becoming a resident of Morrisania. He died in 1816.

GOUVERNEUR MORRIS, of Pennsylvania, was born in Morrisania. N.Y., in 1752. He enjoyed the best education that the colonies afforded, and graduated with high honors from Columbia College at the age of sixteen years. Then he studied law in the office of Wm. Smith, a well-known barrister, who afterwards became Chief Justice of the Province of New York. At the age of nineteen years, in 1771, he was admitted to the Provincial bar. In 1775, after devoting a great deal of attention to public affairs, Mr. Morris was elected a member of the Provincial Congress, and three years later was sent to the Continental Congress. The delegates of New York were not empowered to sign the Declaration of Independence until after the meeting of the State Convention on July 9, 1776. On that day the convention having received a copy of the Declaration passed a resolution of approval, and directed Governeur Morris to write an answer notifying the delegates of this action. Mr. Morris was known as one of the earliest opponents of domestic slavery in New York State, and look a large part in drafting the Constitution of that State. In 1778, as a member of Congress, he was made a mem her of several committees on military supplies, and became a C1ose personal friend of General Washington. Deserted by his own family because of his zeal in behalf of the patriot cause, he made up his mind to take up a permanent residence in Philadelphia. He lost a leg because of an accident in 1780. He was Assistant Superintendent of Finance under Robert Morris for three and a half years. In 1788, he went to France, and was the only member of the diplomatic corps who remained in Paris. On his return to America he was elected a member of the United States Senate from New York, after again becoming a resident of Morrisania. He died in 1816.

WILLIAM LIVINGSTON – NEW JERSEY

WILLIAM LIVINGSTON, of New Jersey, was born in 1723, at Albany, New York. In company with a missionary, he spent some years of his boyhood life with the Mohawk Indians, but during that period his studies were not neglected, and at the age of a little over fifteen years, in 1737, he entered Yale College, immediately taking high rank in his class and graduating at its head. He studied law in the office of James Alexander in New York City. His circumstances were easy, and his law practice did not interfere with a great deal of literary work and political effort, for which Mr. Livingston was admirably adapted. He engaged in polemical controversies with the leading minds of his day, and his poems are among the most graceful, as well as the most spirited effusions of America’s earlier literature. He did not go into political life until after his removal from New York to New Jersey, where he was elected in 1784 to represented the latter State in the Continental Congress. In 1775 he was made a Brigadier-General in command of all the New Jersey forces, and in 1776 was elected Governor, in which capacity it is relate] that he refused the position of Postmaster to a certain applicant because the latter had refused to accept Continental money. During the Revolution the biting sarcasm of Livingston’s pen exasperated the Tories, and many unavailing efforts were made by British troops to seize his person. In 1785 he declined appointment by Congress as Minister to Holland. After 1787 he was again chosen Governor of New Jersey, and died in 1790 while holding that office.

WILLIAM LIVINGSTON, of New Jersey, was born in 1723, at Albany, New York. In company with a missionary, he spent some years of his boyhood life with the Mohawk Indians, but during that period his studies were not neglected, and at the age of a little over fifteen years, in 1737, he entered Yale College, immediately taking high rank in his class and graduating at its head. He studied law in the office of James Alexander in New York City. His circumstances were easy, and his law practice did not interfere with a great deal of literary work and political effort, for which Mr. Livingston was admirably adapted. He engaged in polemical controversies with the leading minds of his day, and his poems are among the most graceful, as well as the most spirited effusions of America’s earlier literature. He did not go into political life until after his removal from New York to New Jersey, where he was elected in 1784 to represented the latter State in the Continental Congress. In 1775 he was made a Brigadier-General in command of all the New Jersey forces, and in 1776 was elected Governor, in which capacity it is relate] that he refused the position of Postmaster to a certain applicant because the latter had refused to accept Continental money. During the Revolution the biting sarcasm of Livingston’s pen exasperated the Tories, and many unavailing efforts were made by British troops to seize his person. In 1785 he declined appointment by Congress as Minister to Holland. After 1787 he was again chosen Governor of New Jersey, and died in 1790 while holding that office.

JONATHAN DAYTON – NEW JERSEY

JONATHAN DAYTON, of New Jersey, was born in 1760, at Elizabethtown, in that colony. He was, of course, a mere boy at the time the Revolutionary war began, but he came of good old Revolutionary stock, and his father, Elias Dayton, was one of the first of the New Jersey patriots to fling down the gauntlet of resistance to royal oppression. The latter entered the army of Washington and was one of the General’s most trusted lieutenants. He rose to the position of colonel, and then to that of general in a very short time. His valor as well as his coolness was displayed upon the field at Brandywine, at Germantown, and at Monmouth. Jonathan, his son, in spite of his youth, insisted on going into the army, and did his own share of the fighting, undergoing at the same time, all the hardships and privations that fell to the lot of the private soldier. He was popular with all who came into contact with him, and a young man of great steadiness or purpose, as well as of ardent patriotism. After the war was over, Jonathan Dayton came into prominence in civic life, and was chosen to a number of offices of strictly local importance, which, nevertheless, brought out into full relief the confidence which his neighbors felt in him. His work in the Constitutional Convention was hard and faithful, though his position was not that of a leader. In 1791 he was sent to Congress as a Federalist. For four years, from 1793 to 1797, he was Speaker of the House, and was then chosen United States Senator. His death occurred in 1824.

JONATHAN DAYTON, of New Jersey, was born in 1760, at Elizabethtown, in that colony. He was, of course, a mere boy at the time the Revolutionary war began, but he came of good old Revolutionary stock, and his father, Elias Dayton, was one of the first of the New Jersey patriots to fling down the gauntlet of resistance to royal oppression. The latter entered the army of Washington and was one of the General’s most trusted lieutenants. He rose to the position of colonel, and then to that of general in a very short time. His valor as well as his coolness was displayed upon the field at Brandywine, at Germantown, and at Monmouth. Jonathan, his son, in spite of his youth, insisted on going into the army, and did his own share of the fighting, undergoing at the same time, all the hardships and privations that fell to the lot of the private soldier. He was popular with all who came into contact with him, and a young man of great steadiness or purpose, as well as of ardent patriotism. After the war was over, Jonathan Dayton came into prominence in civic life, and was chosen to a number of offices of strictly local importance, which, nevertheless, brought out into full relief the confidence which his neighbors felt in him. His work in the Constitutional Convention was hard and faithful, though his position was not that of a leader. In 1791 he was sent to Congress as a Federalist. For four years, from 1793 to 1797, he was Speaker of the House, and was then chosen United States Senator. His death occurred in 1824.

GUNNING BEDFORD – DELAWARE

GUNNING BEDFORD, JR., of Delaware, was a native of Philadelphia, and was born in 1747. He was of pure English descent, and a man of considerable influence in the little colony to which he removed. He had enjoyed a good education at one of the smaller colleges which had sprung up in New Jersey, having graduated from Nassau Hall in 1771, with the highest honors of his class. Very little else is known about Bedford’s youth, but it would not appear that he was a precocious boy, for he must have been twenty-four years of age at the time he received the degree of Master of Arts, and before he was able to begin his study of the law. He went at once into an office in Philadelphia, which might fairly be regarded as the centre of legal culture at that period, illustrious in the mother country. After admission to the bar, Bedford soon took up his residence in Delaware, and it as not long before he had secured a first class practice. He was a sterling patriot throughout the Revolutionary period, and was chosen by his fellow citizens to several places of trust: Attorney-General, member of the Legislature, and member of Congress. He had the confidence of Washington, and after the adoption of the Constitution was appointed by the latter as the first Judge of the District Court of the United States for the district of Delaware. He was an exemplary man in every way, and one who commanded the universal respect of those who knew him. Bedford held the office of District Judge until his death, which occurred in 1812, just before the beginning of the second war with England.

GUNNING BEDFORD, JR., of Delaware, was a native of Philadelphia, and was born in 1747. He was of pure English descent, and a man of considerable influence in the little colony to which he removed. He had enjoyed a good education at one of the smaller colleges which had sprung up in New Jersey, having graduated from Nassau Hall in 1771, with the highest honors of his class. Very little else is known about Bedford’s youth, but it would not appear that he was a precocious boy, for he must have been twenty-four years of age at the time he received the degree of Master of Arts, and before he was able to begin his study of the law. He went at once into an office in Philadelphia, which might fairly be regarded as the centre of legal culture at that period, illustrious in the mother country. After admission to the bar, Bedford soon took up his residence in Delaware, and it as not long before he had secured a first class practice. He was a sterling patriot throughout the Revolutionary period, and was chosen by his fellow citizens to several places of trust: Attorney-General, member of the Legislature, and member of Congress. He had the confidence of Washington, and after the adoption of the Constitution was appointed by the latter as the first Judge of the District Court of the United States for the district of Delaware. He was an exemplary man in every way, and one who commanded the universal respect of those who knew him. Bedford held the office of District Judge until his death, which occurred in 1812, just before the beginning of the second war with England.

CHARLES PINCKNEY – SOUTH CAROLINA

CHARLES PINCKNEY, of South Carolina, was born at Charleston in 1758. He received as good an education as his native town afforded and then studied law in the office of his father. He was chosen a member of the State Legislature in 1779, and one year later was made a prisoner by the British forces. He too experienced the harshest treatment from his captors. Sent to St. Augustine, Fla., soon after his capture, he was for a considerable time confined on board a prison ship. After the war had ended, he returned to the Charleston bar, but in 1785 was chosen to represent his State in Congress, a position which he held for three years. During that period he served as a member of the Constitutional Convention with great honor to himself and with credit to his State. A form of government, drawn up by Charles Pinckney, was one of the sources from which the Constitution was compiled, and it may fairly be said that he showed greater powers of constructive statesmanship than any other of the distinguished men who made up the South Carolina delegation. In the State Convention, called to ratify the Constitution, he was one of the ablest speakers in its favor. He was chosen Governor in 1789, and in 1790 was President of the Constitutional Convention. He served as Governor until 1798, and was then elected to the United States Senate. In 1801 he was made minister to Spain. In 1805 he became a member of Congress and was an active opponent of the Missouri Compromise, against which he made a speech whcih was regarded by his colleagues as the most effective of his life. He died in 1824.

CHARLES PINCKNEY, of South Carolina, was born at Charleston in 1758. He received as good an education as his native town afforded and then studied law in the office of his father. He was chosen a member of the State Legislature in 1779, and one year later was made a prisoner by the British forces. He too experienced the harshest treatment from his captors. Sent to St. Augustine, Fla., soon after his capture, he was for a considerable time confined on board a prison ship. After the war had ended, he returned to the Charleston bar, but in 1785 was chosen to represent his State in Congress, a position which he held for three years. During that period he served as a member of the Constitutional Convention with great honor to himself and with credit to his State. A form of government, drawn up by Charles Pinckney, was one of the sources from which the Constitution was compiled, and it may fairly be said that he showed greater powers of constructive statesmanship than any other of the distinguished men who made up the South Carolina delegation. In the State Convention, called to ratify the Constitution, he was one of the ablest speakers in its favor. He was chosen Governor in 1789, and in 1790 was President of the Constitutional Convention. He served as Governor until 1798, and was then elected to the United States Senate. In 1801 he was made minister to Spain. In 1805 he became a member of Congress and was an active opponent of the Missouri Compromise, against which he made a speech whcih was regarded by his colleagues as the most effective of his life. He died in 1824.

WILLIAM FEW – GEORGIA

WILLIAM FEW, of Georgia, was a native of Maryland, and was born in Baltimore County, in 1748. When he was ten years of age his father’s family removed to the State of North Carolina. His early youth was hampered by the severest influences of poverty, and he was given the advantage of only a year’s attendance at the village school. The son of a farmer, he was expected to give all his time to the daily tasks laid out for him, and no boy of the time ever struggled harder for an opportunity to improve himself. The books that came into his hands were very few, but moved by an insatiable anxiety to learn, he spent all of his spare time to study. He used to attend the sessions of the County Court when he could get a chance to do so, and it was there that he gained the first rudiments of legal knowledge. In 1776 he removed to Georgia, and soon afterwards was chosen a member of the Executive Council. He joined the militia force of Georgia when the State was invaded and was made Lieutenant-Colonel of a Richmond County regiment. From 1778 to 1780 he was a member of the State Legislature, and then served in Congress until 1783. He was re-elected to Congress in 1786, and in the same year chosen a member of the Constitutional Convention. He served as United States Senator from Georgia from 1789 to 1793. He then began the practice of law, and in 1799 decided to remove to the State of New York, when he took up his residence at Fishkill. From 1801 to 1804 he served in the Legislature of the Empire State. He died in 1828.

WILLIAM FEW, of Georgia, was a native of Maryland, and was born in Baltimore County, in 1748. When he was ten years of age his father’s family removed to the State of North Carolina. His early youth was hampered by the severest influences of poverty, and he was given the advantage of only a year’s attendance at the village school. The son of a farmer, he was expected to give all his time to the daily tasks laid out for him, and no boy of the time ever struggled harder for an opportunity to improve himself. The books that came into his hands were very few, but moved by an insatiable anxiety to learn, he spent all of his spare time to study. He used to attend the sessions of the County Court when he could get a chance to do so, and it was there that he gained the first rudiments of legal knowledge. In 1776 he removed to Georgia, and soon afterwards was chosen a member of the Executive Council. He joined the militia force of Georgia when the State was invaded and was made Lieutenant-Colonel of a Richmond County regiment. From 1778 to 1780 he was a member of the State Legislature, and then served in Congress until 1783. He was re-elected to Congress in 1786, and in the same year chosen a member of the Constitutional Convention. He served as United States Senator from Georgia from 1789 to 1793. He then began the practice of law, and in 1799 decided to remove to the State of New York, when he took up his residence at Fishkill. From 1801 to 1804 he served in the Legislature of the Empire State. He died in 1828.

JARED INGERSOLL – PENNSYLVANIA

JARED INGERSOLL, of Pennsylvania, was born in 1750, at New Haven, Connecticut. He was the son of one of the most ardent patriots of the land of steady habits, and after receiving a thorough education, had spent some years in England in the study of his profession. He early showed talents calculated to make him a leading light at the bar, and his eloquence was famed throughout the country, when at the age. of 28 years, in 1778, he was induced to remove to Philadelphia. Mr. Ingersoll did not hesitate to avow himself an adherent of the Colonial cause, and he was one of the numerous solid men of Philadelphia who gave to the patriotic party in that city a social standing far superior to that which it enjoyed in New York or even in Boston. He did not at first approve of the idea of absolute independence from Great Britain, but the logic of events soon brought him over to that side of the question. He never held any position in connection with the general government, either before or after the sessions of the Constitutional Convention. He never held any other place in any popular or representative body. In that Convention he spoke but little. When he said anything it was on behalf of the Hamiltonian theory of government so generally favored by the Pennsylvania delegates. Mr. Ingersoll is looked upon as having been the best lawyer of his time in the management of a jury trial. He was the first Attorney General of Pennsylvania, and held the place under Gov. Mifflin for nine years. For a short time he was President of the District Court of Philadelphia. He died in 1822.

JARED INGERSOLL, of Pennsylvania, was born in 1750, at New Haven, Connecticut. He was the son of one of the most ardent patriots of the land of steady habits, and after receiving a thorough education, had spent some years in England in the study of his profession. He early showed talents calculated to make him a leading light at the bar, and his eloquence was famed throughout the country, when at the age. of 28 years, in 1778, he was induced to remove to Philadelphia. Mr. Ingersoll did not hesitate to avow himself an adherent of the Colonial cause, and he was one of the numerous solid men of Philadelphia who gave to the patriotic party in that city a social standing far superior to that which it enjoyed in New York or even in Boston. He did not at first approve of the idea of absolute independence from Great Britain, but the logic of events soon brought him over to that side of the question. He never held any position in connection with the general government, either before or after the sessions of the Constitutional Convention. He never held any other place in any popular or representative body. In that Convention he spoke but little. When he said anything it was on behalf of the Hamiltonian theory of government so generally favored by the Pennsylvania delegates. Mr. Ingersoll is looked upon as having been the best lawyer of his time in the management of a jury trial. He was the first Attorney General of Pennsylvania, and held the place under Gov. Mifflin for nine years. For a short time he was President of the District Court of Philadelphia. He died in 1822.

NATHANIEL GORHAM – MASSACHUSETTS

NATHANIEL GORHAM, of Massachusetts, was born at Charlestown in 1738. He attended the common schools, but did not receive a university education, and early entered business in his native town. He won the esteem of his fellow citizens, and was made a Town Councillor in 1771 at a time when the spirit of resistance to tyranny was just beginning to ferment in the bosom of the Bay State men, preparing them for the stirring events of Concord and Lexington and Bunker Hill. Then Mr. Gorham became a member of the Legislature, and afterwards a member of the State Board of War, in which he took an active part in raising resources for carrying on the war. He was a delegate to the State Constitutional Convention in 1779, and President of Congress from 1785 to 1787. In the Constitutional Convention he played an important part owing to the desire of General Washington to take part in debate upon the floor. The latter asked Mr. Gorham to take the chair while the body was in Committee of the Whole. For three months the Massachusetts delegate proved himself an efficient, firm and temperate presiding officer, and justified the trust reposed in him by the great Virginian. After the work of the Convention was over Mr. Gorham did good work in securing the adoption of the Constitution by his own State. He was elected a judge of the Court of Common Pleas, and retained that office until his death on June 11, 1796.

NATHANIEL GORHAM, of Massachusetts, was born at Charlestown in 1738. He attended the common schools, but did not receive a university education, and early entered business in his native town. He won the esteem of his fellow citizens, and was made a Town Councillor in 1771 at a time when the spirit of resistance to tyranny was just beginning to ferment in the bosom of the Bay State men, preparing them for the stirring events of Concord and Lexington and Bunker Hill. Then Mr. Gorham became a member of the Legislature, and afterwards a member of the State Board of War, in which he took an active part in raising resources for carrying on the war. He was a delegate to the State Constitutional Convention in 1779, and President of Congress from 1785 to 1787. In the Constitutional Convention he played an important part owing to the desire of General Washington to take part in debate upon the floor. The latter asked Mr. Gorham to take the chair while the body was in Committee of the Whole. For three months the Massachusetts delegate proved himself an efficient, firm and temperate presiding officer, and justified the trust reposed in him by the great Virginian. After the work of the Convention was over Mr. Gorham did good work in securing the adoption of the Constitution by his own State. He was elected a judge of the Court of Common Pleas, and retained that office until his death on June 11, 1796.

NICHOLAS GILMAN – NEW HAMPSHIRE

THE youngest member of the Convention was NICHOLAS GILMAN, of New Hampshire. He was born in 1762, and was a son of Nicholas Gilman, State Treasurer of New Hampshire. Mr. Gilman, though but 25 years of age, impressed himself upon his colleagues in the Constitutional Convention by his grasp of the questions involved, as well as by the fervency of his patriotism. He was at that time a lawyer in first-rate practice in his own State, and is said to have been one of the best in the country. Those who saw him for the first time, thought him only a boy. His face had none of the hardened lines of mature manhood, but when he took part in conversation or in debate everyone was surprised at the comprehensive knowledge and sound sense displayed by this youthful son of the Granite State. A mere child at the time when the Revo1utionary Rubicon was passed in 1776, he had about him non of the traditional feelings of a man who had once owed allegiance to an English King. He represented Young America in what may now be regarded, in the light of the results, as the greatest of all the deliberative bodies whose sessions are mentioned in the world’s history. Mr. Gilman was elected to the First Federal Congress, and served in the capacity of Congressman till 1797. In 1805 he became United States Senator and held that position until his death, which occurred at the age of 52 years, on May 2, 1814.

THE youngest member of the Convention was NICHOLAS GILMAN, of New Hampshire. He was born in 1762, and was a son of Nicholas Gilman, State Treasurer of New Hampshire. Mr. Gilman, though but 25 years of age, impressed himself upon his colleagues in the Constitutional Convention by his grasp of the questions involved, as well as by the fervency of his patriotism. He was at that time a lawyer in first-rate practice in his own State, and is said to have been one of the best in the country. Those who saw him for the first time, thought him only a boy. His face had none of the hardened lines of mature manhood, but when he took part in conversation or in debate everyone was surprised at the comprehensive knowledge and sound sense displayed by this youthful son of the Granite State. A mere child at the time when the Revo1utionary Rubicon was passed in 1776, he had about him non of the traditional feelings of a man who had once owed allegiance to an English King. He represented Young America in what may now be regarded, in the light of the results, as the greatest of all the deliberative bodies whose sessions are mentioned in the world’s history. Mr. Gilman was elected to the First Federal Congress, and served in the capacity of Congressman till 1797. In 1805 he became United States Senator and held that position until his death, which occurred at the age of 52 years, on May 2, 1814.

WILLIAM PATERSON – NEW JERSEY

WILLIAM PATERSON, of New Jersey, was born in Ireland in 1744. He was but two years of age when his parents came to America. They settled at Trenton, and it was there that the early youth of their son was passed. He attended the public schools at Trenton, and afterward at Princeton and Raritan, now known as Somerville, to which the family successively removed. Then he went to Princeton College, and in 1763 graduated with high honors. He studied law with Richard Stockton, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and soon secured a good practice. He was elected a member of the Continental Congress in 1775 and became the Attorney General of his State one year later. Elected a member of Congress again and then elected, he resigned in 1783 to return to his legal work. He was looked upon as leader among the delegates of New Jersey to the Constitutional Convention, and was the sponsor of that “New Jersey” form of Government which was finally adopted with modifications, and which preserved the sovereignties of the States, in contradistinction to the “Virginia” plan, which was offered by Edmund Randolph, and which, in effect, established a national and centralized government. After the adoption of the Constitution, Mr. Paterson was elected United States Senator, then Governor of the State, and at length was appointed a Judge on the bench of the United States Supreme Court, which position he was filling at the time of his death in the year 1806.

WILLIAM PATERSON, of New Jersey, was born in Ireland in 1744. He was but two years of age when his parents came to America. They settled at Trenton, and it was there that the early youth of their son was passed. He attended the public schools at Trenton, and afterward at Princeton and Raritan, now known as Somerville, to which the family successively removed. Then he went to Princeton College, and in 1763 graduated with high honors. He studied law with Richard Stockton, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and soon secured a good practice. He was elected a member of the Continental Congress in 1775 and became the Attorney General of his State one year later. Elected a member of Congress again and then elected, he resigned in 1783 to return to his legal work. He was looked upon as leader among the delegates of New Jersey to the Constitutional Convention, and was the sponsor of that “New Jersey” form of Government which was finally adopted with modifications, and which preserved the sovereignties of the States, in contradistinction to the “Virginia” plan, which was offered by Edmund Randolph, and which, in effect, established a national and centralized government. After the adoption of the Constitution, Mr. Paterson was elected United States Senator, then Governor of the State, and at length was appointed a Judge on the bench of the United States Supreme Court, which position he was filling at the time of his death in the year 1806.

RICHARD BASSETT – DELAWARE

RICHARD BASSETT was the only member of the Delaware delegation to the Constitutional Convention who was born in the territory now comprised in that State. He was, like Bedford, a lawyer in good practice, at the beginning of the Revolution, and was a member of Congress during the Confederation period was for a long time in close correspondence with the most prominent men of his day, and from 1783 up to the adoption of the Constitution, his correspondence had borne upon the topics so close to the hearts of all real statesmen of that age- the establishment of a more satisfactory form of Union. Like, Washington and Hamilton and Franklin, he was deeply impressed with the dangers to be anticipated from the laxness of the Confederation. He was made one of the Delaware Commissioners to the Annapolis Convention 1786, and there had an opportunity to personally compare views with those men whom he had corresponded with. In the Constitutional Convention he devoted most of his energies to securing for Delaware and other small States an equal representation in the Senate of the United States. He was elected United States Senator, but resigned to take the place of Chief Justice of the State Court of Common Pleas. As a Presidential elector, in 1797, he cast his vote for John Adams, the Federalist candidate. From 1798 to 1801 he was Governor of his State. He then became a United States Circuit Judge. Richard Bassett’s daughter married James A. Bayard, afterwards a United States Senator, and he was, therefore a direct ancestor of the historic family of Bayards, to which ex-Secretary of State Bayard belongs. He died in 1815.

RICHARD BASSETT was the only member of the Delaware delegation to the Constitutional Convention who was born in the territory now comprised in that State. He was, like Bedford, a lawyer in good practice, at the beginning of the Revolution, and was a member of Congress during the Confederation period was for a long time in close correspondence with the most prominent men of his day, and from 1783 up to the adoption of the Constitution, his correspondence had borne upon the topics so close to the hearts of all real statesmen of that age- the establishment of a more satisfactory form of Union. Like, Washington and Hamilton and Franklin, he was deeply impressed with the dangers to be anticipated from the laxness of the Confederation. He was made one of the Delaware Commissioners to the Annapolis Convention 1786, and there had an opportunity to personally compare views with those men whom he had corresponded with. In the Constitutional Convention he devoted most of his energies to securing for Delaware and other small States an equal representation in the Senate of the United States. He was elected United States Senator, but resigned to take the place of Chief Justice of the State Court of Common Pleas. As a Presidential elector, in 1797, he cast his vote for John Adams, the Federalist candidate. From 1798 to 1801 he was Governor of his State. He then became a United States Circuit Judge. Richard Bassett’s daughter married James A. Bayard, afterwards a United States Senator, and he was, therefore a direct ancestor of the historic family of Bayards, to which ex-Secretary of State Bayard belongs. He died in 1815.

ABRAHAM BALDWIN – GEORGIA

ABRAHAM BALDWIN, of Georgia, was a native of Connecticut, born in 1754. He fitted for college in the village school, and entered Yale College in 1768, graduating therefrom in 1772. From 1775 to 1779 he served as tutor in the same institution, and in 1781 declined both the Professorship of Divinity and the position of College Pastor. For a very short time he was chaplain of a regiment in the Colonial army. He opened a school of his own and spent all the time he had to spare in studying law. His emigration to Georgia took place in 1784, and soon after securing citizenship there, he was admitted to the bar. That he made friends very rapidly among his new neighbors is attested by the fact that he was elected to the Legislature within three months after his admission to the bar. In the Legislature he introduced a bill to incorporate the University of Georgia at Milledgeville, and on the campus of that institution he shares with John Milledge, its founder, the honor of a marble- pillar erected to commemorate their services. For a time Baldwin was president of the college. In 1785 he was elected to Congress. He was a warm friend of the Constitution, but after it had been adopted became a member of the Strict- Construction or Democratic Party. He served in Congress till 1799, and in the United States Senate until 1807. The poet Joel Barlow was a brother-in-law of Baldwin, and Henry Baldwin, a Judge of the United States Supreme Court was his half-brother. Senator Baldwin appears to have enjoyed the universal confidence of the people of Georgia. He died at Washington on March 4, 1807.

ABRAHAM BALDWIN, of Georgia, was a native of Connecticut, born in 1754. He fitted for college in the village school, and entered Yale College in 1768, graduating therefrom in 1772. From 1775 to 1779 he served as tutor in the same institution, and in 1781 declined both the Professorship of Divinity and the position of College Pastor. For a very short time he was chaplain of a regiment in the Colonial army. He opened a school of his own and spent all the time he had to spare in studying law. His emigration to Georgia took place in 1784, and soon after securing citizenship there, he was admitted to the bar. That he made friends very rapidly among his new neighbors is attested by the fact that he was elected to the Legislature within three months after his admission to the bar. In the Legislature he introduced a bill to incorporate the University of Georgia at Milledgeville, and on the campus of that institution he shares with John Milledge, its founder, the honor of a marble- pillar erected to commemorate their services. For a time Baldwin was president of the college. In 1785 he was elected to Congress. He was a warm friend of the Constitution, but after it had been adopted became a member of the Strict- Construction or Democratic Party. He served in Congress till 1799, and in the United States Senate until 1807. The poet Joel Barlow was a brother-in-law of Baldwin, and Henry Baldwin, a Judge of the United States Supreme Court was his half-brother. Senator Baldwin appears to have enjoyed the universal confidence of the people of Georgia. He died at Washington on March 4, 1807.

JOHN RUTLEDGE – SOUTH CAROLINA

JOHN RUTLEDGE, of South Carolina, was born in 1736, and was the son of parents who had come to this country from Ireland. Of all the representatives of the South he was the most eloquent, and his influence on the Constitutional Convention was a positive one. He had had an excellent classical education, and had studied law in the Temple in London before he settled down to legal practice in Charleston, where he soon secured a large and influential clientage. He was chosen a member of the Congress that met in New York in 1765, and in that body was one of the most fearless as well as one of the most effective speakers in denunciation of the Stamp Act and of all similar forms of British oppression. His next appearance in public life was in the capacity of a member of the Continental Congress in 1774. For two years he held this position, but the time was coming when his State could make even better use of such a man as Rutledge. Elected President and Commander-in-Chief of the forces in South Carolina he wrote the famous note to Col. Moultrie in command of Sullivan’s Island: “General Lee wishes you to evacuate the fort. You will not, without an order from me. I would sooner cut off my hand than write one.” He was elected Governor under the new Constitution in 1778 sent to Congress in 1782, and declined the position of Minister Plenipotentiary to Holland in 1783. Under the Federal Constitution Rutledge was made, in 1789, a Justice of the United States Supreme Court. He resigned to become Chief Justice of South Carolina, and was afterwards appointed Chief Justice of the United States. He died in 1800.

JOHN RUTLEDGE, of South Carolina, was born in 1736, and was the son of parents who had come to this country from Ireland. Of all the representatives of the South he was the most eloquent, and his influence on the Constitutional Convention was a positive one. He had had an excellent classical education, and had studied law in the Temple in London before he settled down to legal practice in Charleston, where he soon secured a large and influential clientage. He was chosen a member of the Congress that met in New York in 1765, and in that body was one of the most fearless as well as one of the most effective speakers in denunciation of the Stamp Act and of all similar forms of British oppression. His next appearance in public life was in the capacity of a member of the Continental Congress in 1774. For two years he held this position, but the time was coming when his State could make even better use of such a man as Rutledge. Elected President and Commander-in-Chief of the forces in South Carolina he wrote the famous note to Col. Moultrie in command of Sullivan’s Island: “General Lee wishes you to evacuate the fort. You will not, without an order from me. I would sooner cut off my hand than write one.” He was elected Governor under the new Constitution in 1778 sent to Congress in 1782, and declined the position of Minister Plenipotentiary to Holland in 1783. Under the Federal Constitution Rutledge was made, in 1789, a Justice of the United States Supreme Court. He resigned to become Chief Justice of South Carolina, and was afterwards appointed Chief Justice of the United States. He died in 1800.

PIERCE BUTLER – SOUTH CAROLINA